Founder’s Statement

MUSICAL BACKGROUND

I began my stage career at age ten, touring domestically and internationally with the American Boychoir. I performed annually in some two hundred concerts offered in venues ranging from Carnegie Hall and Boston Symphony Hall to churches in remote rural communities. These formative years did more than instill a love of rich vocal harmony, or spark my wish to work in the performing arts. I also learned at first hand how high youth can rise when properly respected and supported by adults. This perspective remains vital to my work as an educator today.

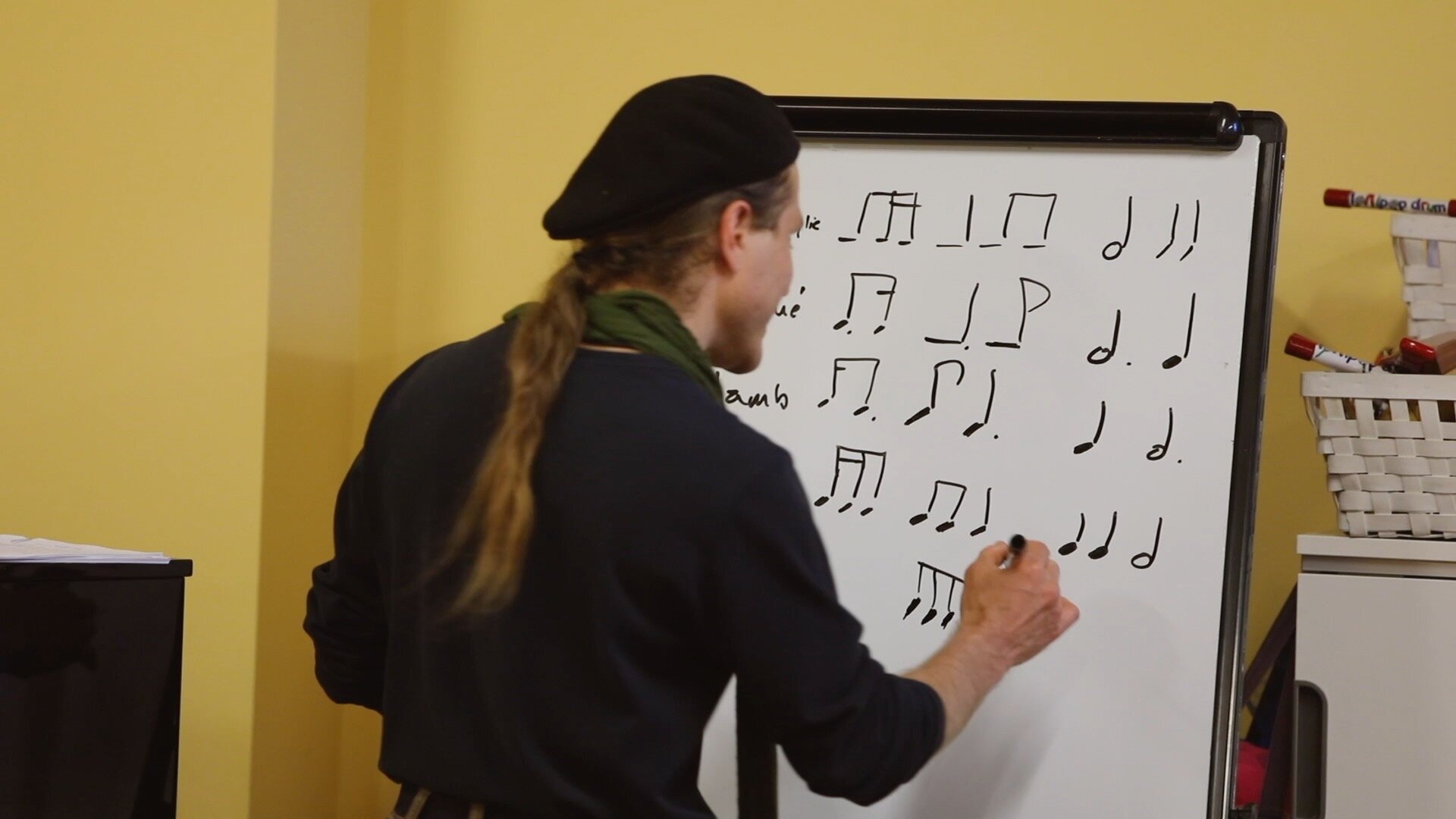

Artistically, I am inexorably fascinated by the ability of music to speak in shades of emotion too subtle to be captured by words. Composition, improvisation and performance are processes for articulating the vast nuance and contradictions of our emotional life, both in voicing my own being and in stirring resonance with audiences’ collective experience. In this sense, musicality is cultivated by striving both for maximal awareness and for ever more subtle tools of expression. The pursuit of music as an emotional language is one of the many reasons that Dalcroze education is both sensible and inspiring. How else to teach a nonverbal, direct emotional language other than giving students intimate experiences of the affect of musical elements? How better to learn this than to first know well the ways musical elements move us?

After graduating the American Boychoir, I continued to explore various musical forms and instruments, from private piano lessons and high level youth jazz bands to undergraduate ethnomusicology courses and a five-year in-depth study of the Hindusthani sitar. My principle guide was my ongoing work as a professional performer. It compelled me, as it were, to seek tools and techniques that would increase what I could offer. Such self-driven, need-based education naturally resulted in learning gaps, as I skirted concepts that were not directly relevant. Thus, for example, it did not cross my mind to teach myself how to harmonize Bach chorales. I first learned to do this as part of my Masters program. Nevertheless, immediate application of newly learned skills was a benefit. Studying towards a Masters of Music and the Dalcroze Certificate sustained my process of applied learning, an education that now continues with the Dalcroze License and Pre-diplôme program with the Dalcroze School of the Rockies.

This education informs my work as Director of Music & Education for my touring ensemble. Together with a love of story and a historical fascination, this background results in shows marrying music with evocative storytelling, transporting audiences to the long-ago-and-far-away in order to ask difficult questions about our own here-and-now. I now stretch my boundaries further by adding visual storytelling in the form of sand animation in a project made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts and The Boston Foundation.

WHY DALCROZE COMPELS ME

My ongoing devotion to Dalcroze training results from two main values: The vitality of lifelong learning, and the importance of contributing to the quality of life of those around me. Both run deep in my family. The belief that being alive means to simultaneously stretch one’s self while giving back to others drove my paternal grandmother’s international organization, Lifeline for the Old. It began by extending the lives, dignity and wellbeing of Israeli and Arab elders by insisting that they continue to serve their communities (largely through the arts and through mentorship of young people) and that they keep honing their personal skills. Likewise, lifelong learning and contribution was one of the essential elements of my maternal grandparents’ innovative home for youth at risk, which later became a model of integrating “troubled kids” into Israeli society. Lifelong learning and contribution were the way my paternal grandfather and aunt stayed engaged and intellectually vibrant late into their nineties, even when physical health failed.

For me, Dalcroze study is a gateway to lifelong learning and service to others. I thrive when I learn, and I constantly seek opportunities to grow. These keep me vibrant and engaged (As well as more humble, I think. It’s harder to be full of one’s self when one is flailing with difficult new challenges). Music is also one of the chief ways that I give, both educationally and through composition and performance. My musicality has grown significantly thanks to my Dalcroze training and, especially, my studies with Lisa Parker and Jeremy Dittus. It is impossible to extricate this growth from my career as performer and educator.

If the motivation to be a high-level music educator begins with the deep pull to the power and mystery of the emotional language of music, it is further propelled by cultural concerns that guided me to Dalcroze in the first place. So many of the young people I meet today seem stuck in an immediate-return consumer lifestyle, where their creation is largely dictated by apps on their phones. This observation is based on interactions with many teenagers with whom I work around the country. For example, alongside artist residencies, I recently designed a long-term experiment in which middle school students were tasked with crafting their own proposals for creative projects that mattered to them, with specific, attainable goals, action steps and measurable mileposts. Again and again I found that even a small failure resulted in abandonment of the endevour altogether rather than the disciplined tenacity to work through the challenge. I became concerned by what I perceived to be a growing lack of resilience, stemming from an underdeveloped skill in pushing one’s self for long stretches of time at the edge of one’s comfort.

The exceptions were most often those who had invested significant time in extra-curricular pursuits, especially the arts, serious martial arts and performance-driven athletics like gymnastics. These students seemed to share several common characteristics. First, they were outliers. Second, they cultivated a relationship with failure by honing their ability to keep themselves on their own cutting edge, working through new, difficult skills systematically until they were reliably replicable. And third, these students tended to get into the best high schools and, in general, to excel in many areas. The relationship between these three traits cannot be over-emphasized. The skill of deliberate practice is essential to meaningful growth in any area. It is a skill that grows with practice. And it is becoming a rare advantage in our age of distraction and immediate gratification.

Music is a wonderful way to teach the skill of deliberate practice. And, when it comes to music, I believe that Dalcroze Education, when taught well, sparks the motivation to practice by enlivening students with music’s vitality and the joy of tapping into their own musical imagination, and by increasing students’ confidence in their abilities to succeed.

-Guy Mendilow, Founder, Dalcroze School of Boston